Each year, our artist development program, Create Change, supports 15 to 20 artists developing their socially engaged creative practice through our Fellowship, Residency, and Commissions program. In 2012, we began asking our Create Change artists to pair up for Creative Conversations: open-ended creative exchanges to be published on our blog. Read on to meet our Create Change alumni.

Nontsi: Social practice implies collaboration between artists and community members. Elizabeth and Hatuey, you chose to build a project together before bringing other people into the equation. What was this experience like?

Elizabeth: Our collaborative work is both arduous and incredibly rewarding. I think that the constant work that is required in order to collaborate with each other is a big influence on the way that we work with other people. Hatuey and I hold each other to very high standards, and the accountability that we demand from one another frames our work in our neighborhood. I really related to Urban Bush Women’s presentation about mutual support through collaboration, and the work that is required to achieve that support–their presentation really articulated things that Hatuey and I have been working on and talking about but had not really been able to make clear for ourselves at that point.

Thinking specifically about neighbors, and neighborhood engagement, can you talk a little about your hair braiding project in Detroit? You were new to that community, but you used the vernacular of hair and braiding as a bridge between a lot of different social, ethnic, and geographic communities.

Nontsi: When I got to Detroit I realised that I had a very short amount of time to meet people in the community, conduct research, make some artwork and organise an event. I started with the people I had connected with on a previous visit and then met others through their network. I collaborated with a barber, ZooNine Bey and former hairstylist Dina Peace. We spent time together before the event talking in depth about our respective work, cultural differences and similarity. Our interactions culminated in a wonderful event where they demonstrated and spoke to me and everyone that came out about their craft. I really acted as a facilitator and allowed talented knowledgeable people to share with others in their community.

I stepped into a place that has a rich history and a strong African-American community committed to presentation, culture and craft. It was a great learning opportunity for me. It was wonderful seeing people coming around to share and be involved with leading and listening.

Elizabeth & Hatuey

Elizabeth & Hatuey: Could you share a specific story from your experience doing this project that really captures that sense of people coming together?

Nontsi: Actually, the best part of the project was when it was all over. People stayed for a long time after we were done, continuing conversations, swapping information asking how and when something similar could be organised again. I am happy that people felt invested.

Elizabeth & Hatuey: On the website “Brainpickings,” there was recently a quote from Bruno Munari (from 1966) that we think is relevant to this discussion. Munari said:

“Today it has become necessary to demolish the myth of the ‘star’ artist who only produces masterpieces for a small group of ultra-intelligent people. It must be understood that as long as art stands aside from the problems of life it will only interest a very few people. Culture today is becoming a mass affair, and the artist must step down from his pedestal and be prepared to make a sign for a butcher’s shop (if he knows how to do it). The artist must cast off the last rags of romanticism and become active as a man among men, well up in present-day techniques, materials and working methods. Without losing his innate aesthetic sense he must be able to respond with humility and competence to the demands his neighbors may make of him.

The designer of today re-establishes the long-lost contact between art and the public, between living people and art as a living thing. … There should be no such thing as art divorced from life, with beautiful things to look at and hideous things to use. If what we use every day is made with art, and not thrown together by chance or caprice, then we shall have nothing to hide.”

Both your practice and ours vacillates between art and design. How do you navigate the differences between those two practices? Does thinking like a designer (rather than an artist) change your perception of “the public” and the way that you participate in public life?

Nontsi: I want to make work that has a space in the world and that can speak to or capture the imagination of people within the space of the museum but more importantly meeting people where they are at. Making things that people can hold in their hands, or focusing on ways of making that borrow from vernacular design and craft has been a way for me to move my work towards people. Sometimes the audience is specific, I aim to create dialog at street level or on the shop floor between my neighbours and peers.

One of the parameters of the Laundromat Project residency is that you produce a project in your very own neighborhood. How long have you been living in the Bronx?

Elizabeth: I have only lived in our neighborhood for about a year. But I don’t see myself going anywhere any time soon.

Hatuey: I’ve been living in the Bronx for 5 years total, 2 years near Yankee Stadium and in Mott Haven 3 years.

Elizabeth & Hatuey: Nontsi, you’re new to New York. How did The Laundromat Project Professional Development Fellowship affect your perception of the city–both as an artist and as an everyday person?

Nontsi: The workshops for the fellowship were held in different Boroughs. Commuting to and from sessions taught me my first lesson about New York – THE PLACE IS HUGE! The population density is incredible and even more so the diversity represented throughout the city. This has really made me reconsider my definition of community. What is a neighbour? What vocabulary, visual or otherwise, do I use to engage them?

Do you feel you had a connection to your community before the Laundromat Project residency?

Elizabeth: Absolutely. We are very lucky to live in a neighborhood with a lot of people who are very committed to achieving social justice through coalition and community-building. We have a lot of neighbors who are organizers and activists, as well as artists, which creates a really amazing space for the kind of work that we do. There are a lot of people who really want to work together.

Hatuey: Yes, we’ve been involved directly and indirectly with this project and other projects as well with our neighbors and organizations. So, we are present.

Nontsi: How did you decide on the issue to tackle for your project? Have you been doing other work around this theme?

Elizabeth: Last spring we did a project called Boogie Down Rides dealing with bicycling as a form of transportation, recreation, and art in the Bronx. We built relationships with a lot of organizations who were dealing with different aspects of the built environment in the Bronx, and we wanted to build on that. But we didn’t feel like bicycling was the right project for The LP.

Hatuey: Also, since we have to be in one place to do the residency (at the laundromat, as opposed to biking around) we chose the waterfront that is within our neighborhood to focus on. So, when we talked about the waterfront with our neighbors they could relate to it or not, but it was something tangible, a specific place that they could go to (even though with difficulty). It is the first time we tackled the idea of the waterfront, but we are interested in places and how they can tells us or give us clues about how they are, the way they are and how they affect, influence and in a way define neighborhoods, boroughs, cities etc

Nontsi: Can you highlight something that you felt was most effective at reaching your goals or fulfilling the needs of the participants?

Hatuey: The goals of the project were to interact with our neighbors about their waterfront, to listen to what they have to say about it and the neighborhood, and to use all of that information for the future. It is hard to meet people’s needs, but at the very least we served as a “channel” for people to tell us things that they saw and wanted to improve and we learned a lot from active listening.

Elizabeth: It’s similar to what you were saying about your project in Detroit– the best moments of the project were when we were talking with our neighbors about the next steps, the future, in our own terms.

Nontsi: Your project seemed interactive on so many levels, could you tell me about the range of activities you set up at the Laundromat?

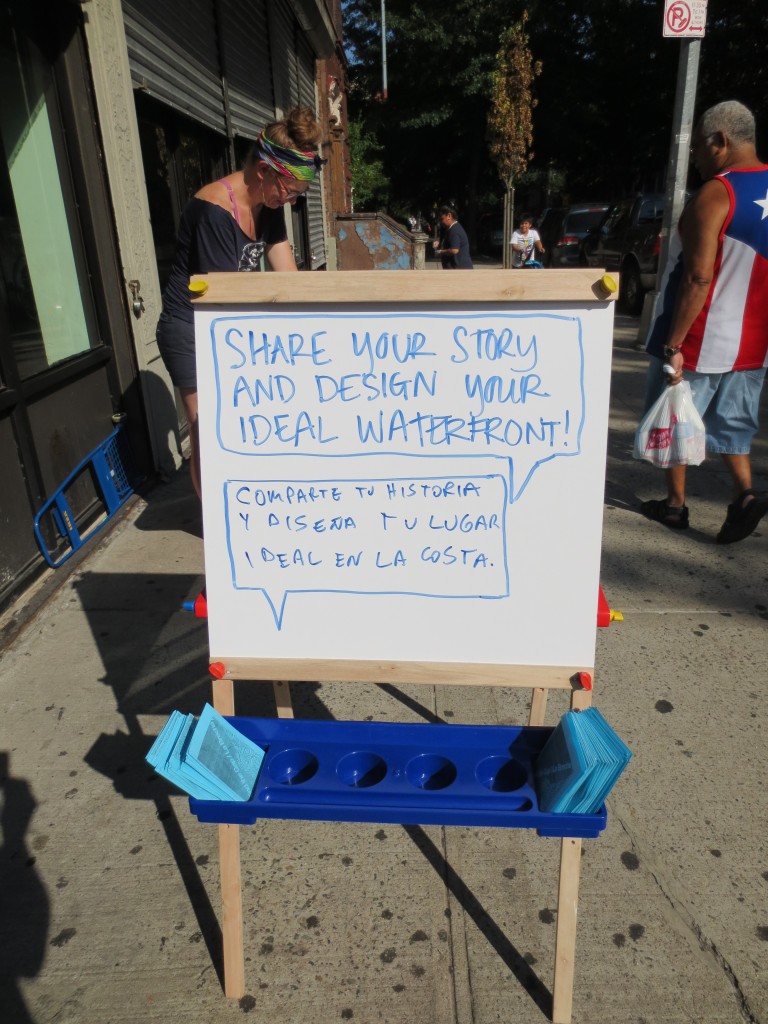

Hatuey: James Rojas, an artist/urban planner, helped us set up an interactive model making project where people came to our table and played with different toys and objects by placing them in different configurations that transformed them from their regular uses into buildings, trees, slides, parks, boardwalks etc… It was the most successful activity since it is very easy to interact with, it is totally non-threatening and can engage multi-generational participants.

We also had a backdrop of a photo of a place within our waterfront and asked people to write on a speech bubble what they wished the place could be and we took portraits of them, we also recorded audio interviews with neighbors about the neighborhood, their stories about the water, etc.

Nontsi: I like the combination of activities you folded into your bigger project. My own work seems to be moving in that direction. The recording of oral history is as important to my investigations as making interactive tools. You’ve mentioned how you worked with participants of all ages. I was very impressed by that. It is so important to harness the energy of all the people to whom a project is relevant.

I also liked how your interactive model utilised everyday objects. This is a great way to get people to feel comfortable with touching and moving pieces around. Also it is a way of working that is not out of the reach for others, the children and adults that participated could easily use this format to extend the work you begun or build their own self-initiated projects.

Elizabeth & Hatuey: It’s similar with your braiding project. Hair braiding is certainly aesthetic and artful, but it is also an activity that takes place within people’s everyday lives. By framing it within an art context, you’re able to simultaneously amplify the “art” of braiding and hair and to (literally as well as metaphorically) weave together art and life.

Nontsi: My own practice as an artist is process-based. Iteration and labour are an important part of all my projects. Braiding embodies these aspects. For me it is very performative, both the learning and practising. It was interesting to see this played out in the space of a museum. I have also been collecting images and objects associated with this craft. It is important to take a close look at things that seem mundane. There is so much richness and variety around us, even in the things that are most familiar to us.

Video about Elizabeth and Hatuey’s project Mind the Gap / La Brecha.

About the Artists

To learn more about Elizabeth and Hatuey’s collaborative work, visit metalocal.net. You can also visit Elizabeth’s site at space-place.net, and Hatuey’s at hatueyramosfermin.com.

To learn more about Elizabeth and Hatuey’s collaborative work, visit metalocal.net. You can also visit Elizabeth’s site at space-place.net, and Hatuey’s at hatueyramosfermin.com.

See more of Nontsi’s work by visiting her artist website.

See more of Nontsi’s work by visiting her artist website.

You can also click here to watch an interview with Nontsi about her ongoing research project investigating the environments and politics of hair.